a discussion of the importance of gesture in ancient Chinese traditions, and its relevance today

In 2006 I spent 3 months in Shanghai as part of a scheme hosted by the British Council. I had already developed an interest in guqin (a seven-stringed Chinese zither) from my earlier residency in Taiwan in 2004 where I had been introduced to its idiosyncrasies, and was keen to learn more, particularly its early notation system (wenzipu). Below is a brief introduction to this ancient notation system with some of my observations in relation to my own interests.

Early guqin notation or wenzipu (文字譜), dating from the Warring States Period (戰國時代) (4th Century), was essentially a narrative—a description of how you physically play a particular work:

‘Take your R.H. 3rd finger and pluck on the 4th position of string number 5…’ etc.

The earliest manuscript of this notation dates from the 6th century, a work called Jieshi Diao Youlan (碣石調幽蘭) literally: “Solitary Orchid in the Stone Tablet Mode”. This notation was time consuming and tedious to learn, so it’s no wonder that later, during the Tang dynasty (618-907AD), these texts became hyphenated. This version was called jianzipu (減字譜).

It’s worth noting that this notation predates even the earliest western music tablature by some hundreds of years.

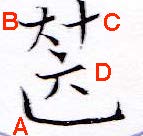

Here is an example:

I’ve circled one in red to use as an example. It looks a bit like a complex Chinese character but you will see each one is made up of several separate bits of information:

The larger/encapsulating part of the character (A) tells you the particular technique to be utilised. There are over 40 of these used today (dozens more in antiquity), most of which include high levels of detail as to their execution (There are over 20 methods of vibrato alone). Here are some of the most common :

Cuo(早)- play by pinching two strings simultaneously

Gou (勹) – middle finger playing towards the body

Pi (尸) – thumb plays towards the body

Da (丁) – ring finger plays towards the body

the symbol here is Tiao(挑), which means the index finger plays towards the ‘hui’/fret point (away from the body),

etc.

The other three parts are all based on either the Chinese number system: 1 一,2二, 3 三,4四, 5五, 6六, 7七, 8八 ,9 九,10十 ….etc. OR the names of each of the 5 fingers: (from the thumb by step) 大食中名跪

So:

(B) – this part tells you which finger to use, in this case the first finger (big finger) or thumb (Da 大)

(C)– this part tells you the point on the string to press, in this case the tenth ‘fret’ point (十)

(D)– and this tells you to use the 6th string(六)

It is also worth noting that this notation decouples the left and right hand actions, both of which have their own distinct lexicon.

What I find most interesting about this notation is that its root priority, which I think is embedded in the notation itself, appears to be the cataloguing of the various physical movements and gestures required to produce the sounds themselves. The actual pitch or rhythm is not specified—all the emphasis is on the physical means of production. Therefore, discrete pitch and rhythm only become clear in the context of the gesture.

Western music notation, by contrast, tends to work in reverse, with most emphasis put on what happens after the gesture has formed (ie, pitch and rhythm). In this case the physical element is only implied.

For the Chinese this connection with the physical is embedded in their culture, in the Zhou dynasty 雅樂 (yayue) was established, a form of classical music integrated with dance. So the character 樂 (yue) could also mean ‘dance’ (or sometimes poetry). The two were considered a binary whole—a duality—music therefore was (perhaps literally) a physical language to the Chinese. Early manuals frequently reference physical movement and gesture in relation to qin pedagogy, often using the movement of animals to capture the essence of a particular technique “a fish flapping its tail” etc. there is an element of the kinaesthetic, tactility and gesture that you dont tend to get in Western music which is reflected in the wenzipu, and in the oral pedagogy that accompanies it.

From the time of Confucius (551–479 BC) the guqin played an integral part of the cultural and philosophical canon of Confucianism, and as such was inseparable from Chinese culture itself. Therefore much symbolism is bestowed upon it: the flat bottom symbolising earth, the rounded top symbolising heaven, the 13 ‘hui’ (fret marks) symbolise the 13 months of the year, or the seasons, the strings (from low to high) represented the social hierarchy, from the law (the lowest string) to the king (highest string). Harmonics represent heaven, the stopped notes represent humour, open strings represent earth, ornaments often represent physical acts such as ‘running’……. etc.

Music was seen as an embodiment of the universe itself, a part of the natural order of things, indeed, playing or making music for mere entertainment was frowned upon and discouraged by the elite, for them, music making was a cerebral activity, an intellectual and social activity, a political activity. This philosophy, combined with all of the symbolism made for remarkably ‘modern’ sounding music for the time.

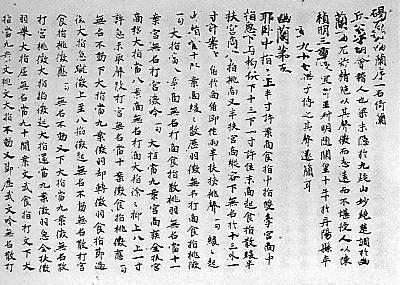

Here is an example:

The manuscript above is from Jieshi Diao Youlan. Listening to a modern interpretation of this work one is struck by the fact that this music doesnt appear to be particularly melodic, so I asked myself if this music could be using abstract symbolism to tell a story by mapping secondary meaning onto pitches and gesture. There is undoubtedly an element of the programatic story telling that characterises qin music from the time, but there is a lot of dissonance and pitch choices which make less musical sense and more ‘symbolic sense’. It is also quite interesting listening to the various ‘reconstructions’ of this work, which serve to remind us of wenzipu’s limitations. Without the oral pedagogy it is very hard to make musical sense of the gestures described in the text, though some of it is made clearer though its context in the piece.

In the process of imagining how an ancient Chinese composer might begin to write a work using these building blocks I came to the conclusion that there must have been some well-established conventions, conventions not just to assist the composer but also the audience to navigate the piece. For instance, a hand sweep over all of the strings might signify eternity, rapid plucking of the highest string might symbolise an angry or grateful king…. we shall probably never properly know, as many of the books, instruments and musical manuscripts were destroyed during the Qin dynasty (221-206 BC) when music was denounced as being a wasteful pastime.

In his thesis Interpreting Histories, Debating Traditions: The Seven-Stringed Zither Qin in Modern Chinese Societies the Taiwanese musicologist Tsan-Huang Tsai discusses the symbolic system of the ancient guqin. What must have happened is the establishment of type of musical syntax, through which music can be created or deciphered based on a generally accepted lexicon. Also, one must then go on to speculate that various combinations of gesture, or pitch would have been established to symbolise more complex images or situations, a type of modular way of working becomes a very distinct possibility, after all, if the music is not intended to be merely entertaining and is made from abstract and symbolic metaphor, there has to have been a concerted attempt to legislate it’s production, its performance practice and its interpretation by the audience.

In the West, aside from a few isolated cases such as JS Bach’s ‘B.A.C.H. motive’, and Schumann’s ‘ciphers’, this sort of ‘lexiconization’ was not considered creatively fertile until the 20th century with the advent of serialism. And of course both Western examples treated pitch itself as ‘concrete’ so the analogy fits only to a certain point. What’s remarkable about this is that we appear to be seeing the emergence of a ‘literal’ language, one where a story can be told and understood in the same way by multiple storytellers and audiences.

Gesture has always been an important element of my own music, so for me it was a revelation to discover a notation system which reflected my interests, in effect, the Jianzipu reminds me very much of the attempts by various 20th century composers, including myself, to decouple the technical and physical elements of playing music…..albeit 1700 years ago.

This article is abridged for the purposes of this web site.

Jeroen Speak March 2017

COPYRIGHT NOTICE All pages and content on this site are subject to copyright and cannot be used for any purpose without the consent of the author.