Jeroen Speak discusses the compositional process and background for his latest collaboration with Forum Music (Taiwan).

Water Song, for guzheng and vibraphone (2023)

I’ve often said about my music that it either goes up or it goes down, occasionally it stands still. And I guess no single work projects this more literally than Water Song. 15 minutes in total length, the work is made up of three movements, the outer two of which explore the complete range of the guzheng (from lower to upper, and upper to lower, respectively) while the inner movement provides a sort of stable point between the ‘gravitational’ pull of the outlying movements.

As implied, this idea isn’t new to my work, but is rarely seen in such stark contrast. The starting point was back in 2004 when I visited the earthquake-ravaged town of Puli close to Sun Moon Lake. I had been invited by Ou Yang Chang Hwa, the commissioner of the Council for Indigenous Peoples to attend a cultural festival. One of the gems of my visit was the first hand exposure to what I have heard called the ‘atonal chord’ (best translation I could find at the time) – a ‘millet harvest song’ sung by the Bunun villagers designed to predict the outcome of the year’s harvest. Traditionally sung by males establishing a consensus on a common (low) chord the individual voices slowly divide as they move upwards in a gradual (uncoordinated) series of steps, jumps and glissandi. This forms very complex, unpredictable, and interesting vertical relationships.

Here is a link to a recording :

(It’s worth noting that this vocal tradition is centuries old, and likely predates 12th century organum.)

When the choir reaches ‘heaven’ (the highest sustainable range of the singers) the performance is complete. If the final chord is a consonant sound then that is considered a good omen. I love the idea of this, and the simplicity of the execution, so I set out to write a piece that contained similar elements. In my work I didn’t want the journey to ‘heaven’ to be quite as direct however: I wanted to plan some ‘side-trips’ along the way by effectively arresting the process at certain points in order to exploit the harmonic tensions and also inject musical and gestural elements that would eventually form the material for the central movement.

The decision to settle on guzheng and vibraphone to explore ideas gleaned from a vocal tradition seems very odd on the surface because neither instrument is practically designed to sustain pitch in the way that a human voice can. This is quirk of my musical way of working: I tend to like the limitations and challenge of trying to do something on the ‘wrong’ instrument. It often creates interesting results and throws up anomalies which I can exploit. Technical considerations aside, I often discover more about an instrument, or combinations of instruments, by approaching them as sonic objects.

(NB: Of course there are fine lines to be negotiated when embarking on cross-cultural projects with regards to ‘cultural authenticity’ and appropriation, something I intend to address in a further article.)

I chose to get around the challenge by instructing both players to use bows; this in turn creates the problem for the Guzheng player in that they no longer have a right hand to use, so all the other demands are placed on the left hand. For the vibraphone player it creates the issue of not having access to the mallets. This has the over-riding effect of imposing limits on the speed of execution of the piece.

The slow tempo of the piece was consequent upon the decision to use bows.

My solution to this problem was preordained: slow the piece down. Hence both outlying movements adopt a sense of being ‘frozen in time’, a sort of induced slow-motion that would not have had the same effect if I’d set out to simply write a slow piece. It ‘sounds’ arrested, it feels like its been pulled apart, literally, as if you could slow a recording down without changing the pitch or the dynamic interrelationship between one tone and the next.

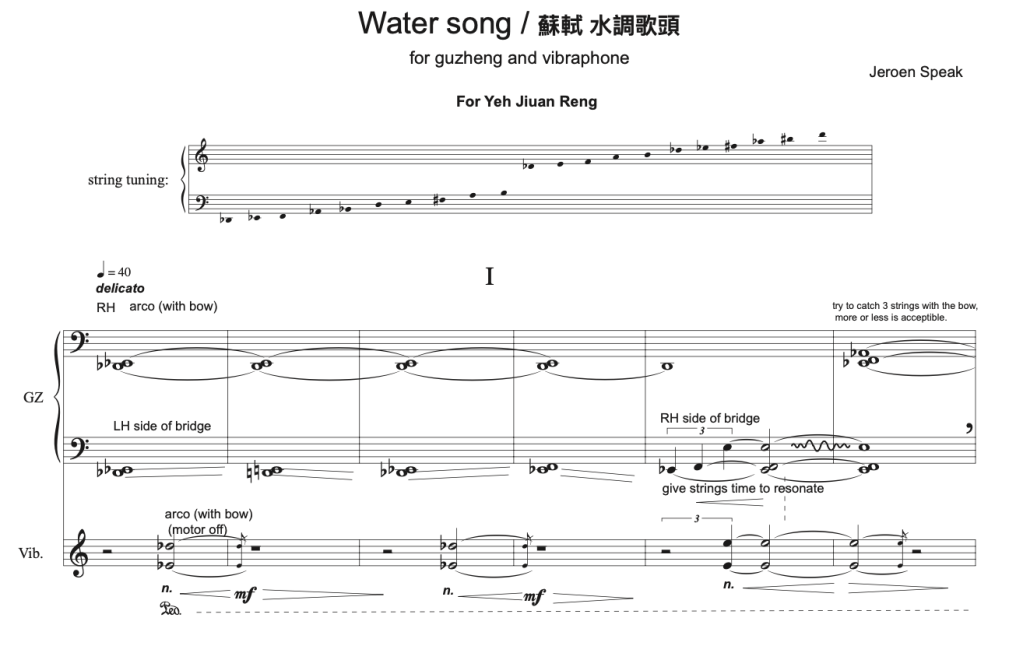

Fig.1 shows the first system of the piece, along with the tuning, which I’ll discuss later. In my notation, the top staff of the guzheng part indicates the actions required of the RH and the lower staff indicates the actions required of the LH: this amounts to a decoupling of the technical elements of the piece, which is crucial because the use of the bow makes it important to clarify which hand is doing what (and where). I conceptualise this as a process of choreography, prioritising the performer’s physical gesture. The role of the vibraphone at the opening is conceived as a sort of augmented envelope that creates the impression of ‘activating the harmonics of the guzheng, effectively providing an ‘acoustic space’ for the ensemble. The delayed/offset reverberation time of the vibraphone’s entries enhances the sense of spatial and temporal expansion.

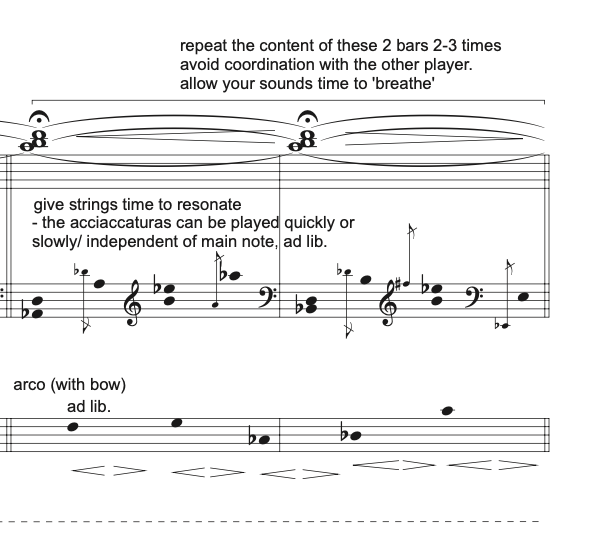

The tuning employed (see top of fig.1) was designed to retain a more or less ‘pentatonic’ distribution in each register while maximising the possibility for dissonance between each of them, a sort of intersection between a ‘traditional-sounding’ tuning and the more grainy effects only possible through discordant sounds. These are the points of harmonic focus I chose to exploit as the register slowly rises and the harmonics become increasingly close together. The relative stability of the opening lower section thus gives way to increasing instability as the growing harmonic tension threatens to break the process altogether, seen in b.21-24 (fig.2).

From this point the guzheng finds its top 3 strings stimulating a kind of ‘ritual’ or a ‘game’ of attacks, decays, harmonics, and space…where the players are allowed a little more freedom to find their own tonal meeting points. (fig.3).

The final movement, which reverses the process (from highest to lowest register) ends with a similar ‘game’ of multi-choice pitches overlapping and emerging from and spilling into each other. These ‘games’ reference both the process at the start and end of the Bunun ‘millet harvest song‘ but also the very real NEED for human ‘consensus’ in a work that describes both a process and a ritual.

Water Song is therefore both a ritual and a process with all of the hallmarks: the processionals both into and out of the space (provided by the outlying movements), and the ‘stabilising’ middle movement, which I’ll come to. (It needs to be noted that the ‘millet harvest song‘ wasn’t just a stand-alone event, it was part of a larger ritual process.)

The opening ‘processional’ is essentially ‘ex hoc mundo’ (from the outside but moving into the realm of reality) establishing the acoustic space and the physical rules and context of the work. The ‘side trips’ I mentioned earlier act like ‘release valves’ from which musical gestures can then escape (from pre conceptual states to articulated gesture): these gestures become the material on which the inner movement is based.

The middle movement thus becomes more literal and grounded, based around the gestures (‘characters’) that emerged in the ‘cracks’ of the procession.

Ancient guqin music (c. 7th century) was characterised by ‘literal’ and often onomatopoeic content it might represent to illustrate characters or events as part of a journey, an heroic quest, or a love story, and sounds of nature. The music of this time found either direct symbolism or musical gestures that best represented the various elements of the narrative. There is still quite limited research into this early repertoire, but it is fairly clear that the guqin held a very special place in the court of post-Confucious dynasties and as such was richly endowed with symbolic meaning. Particular strings, or positions on those strings, symbolised certain things, like the emperor, or the empress, the heavens, luck, wealth, etc. The body of the instrument itself was symbolised. These references were completely abstract and used in addition to the musical (gestural) elements to convey meaning through the composition. You had to be well-versed in this cultural canon to fully appreciate a traditional guqin recital in the 13th century!

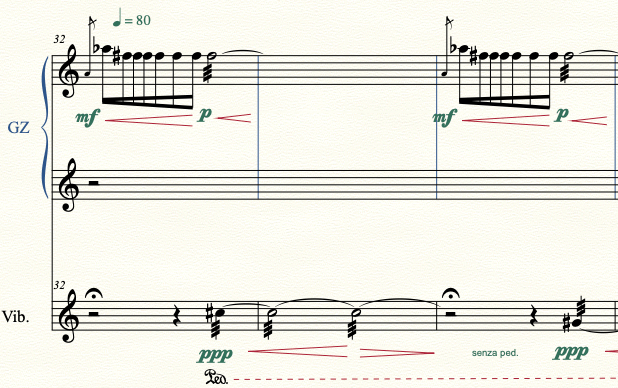

The middle section of my work reinvents this genre, and there is a loose association to one the earliest recorded quin melodies: 獲麟 (Hou Lin, ‘Captured Unicorn’), according to legend, composed by Confucious himself. The material emerges from the seeds of the gestures emerging in the opening procession, starting with the repeated note motive (fig.2) which transforms in to a tremolando in the opening bars (fig.4) symbolising the transition from the ‘pre-conceptual’ to the articulated (or perhaps the mythological to the ‘real’):

The narrative thus becomes a more ‘familiar’ play between the instruments, rather than providing acoustic space, the vibraphone interacts and co-develops the underlying gestural language. This is not a transcription of the original melody, but rather an entirely new depiction of a Confucian-era story ending with the anger and sadness of Confucious as he considers the sad tragedy of the unicorns untimely demise.

here is a link to the performance of Water Song:

The final question might be; why the title ‘Water Song’ ? This has more to do with the quality of the sound world I have created rather than the ideas and musical content. When I was a child I spent a lot of time swimming in the harbour, and it struck me that the sounds invoked by my approach to slow time in this work reminded me of the sounds I heard beneath the water, muffled, indistinct and merging together.

Jeroen Speak 2024