Tuning

The guzheng is a 21-string zither with moveable bridges. The conventional tuning is pentatonic (5 pitches per octave, with the same tuning in each octave). The strings are tuned using a tuning key to adjust the pins hidden in a compartment at the RH end of the instrument. The bridges can be moved for fine adjustment. The guzheng uses the grand staff (the same as the piano).

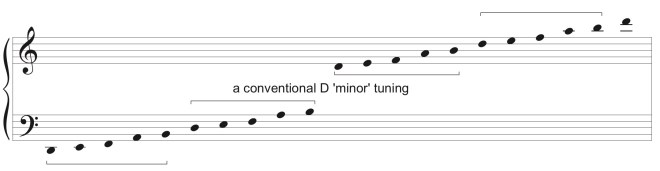

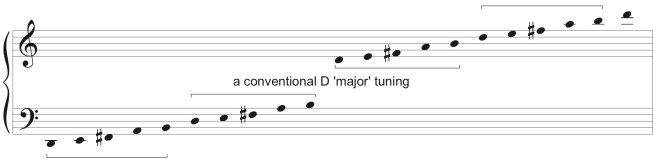

Here is a standard guzheng ‘D major’ and ‘d minor’ tuning:

The tuning of the guzheng is one of the first aspects of the instrument that is open for modification or experimentation: each string can be tuned differently, without the need for uniformity across the octaves. Each composer essentially builds their own ‘instrument’ for each new work.

Jeroen Speak: Silk Dialogues VII

Jeroen Speak’s design for Silk Dialogues VII makes pentatonic, whole-tone and chromatic harmonies available without the instrument having to be re-tuned. The tuning is more-or-less pentatonic in each octave, but is slightly distorted: for example, the second octave is displaced by a semitone, so that it sounds a minor 9th above the first octave (instead of an octave). The tuning doesn’t deviate more than a semitone beyond the ‘natural’ tuning for each string, which retains uniform string tension allowing the instrument to resonate as authentically as possible, while also maximising the possibility for dissonance and tonal colour between registers.

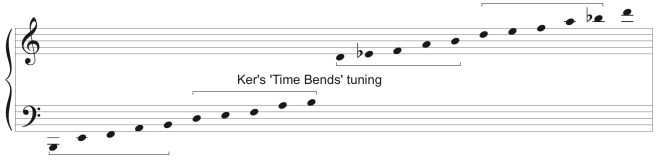

Dorothy Ker: Time Bends in the Rock

Dorothy Ker’s tuning design for Time Bends in the Rock brings the tessitura of the guzheng to a closer proximity with the cello: the low B is just below the cello’s low C string and has a rich, dark quality. By mapping closely to the ‘d minor’ tuning it features semitone steps, to which two more having been added, including the D-E flat ‘node’ in the middle of the range. Combined with the bending technique (bending up of the D string), an indeterminate pitch space ‘between’ the two fixed notes is released. This D-E flat node is linked to the opening and closing gestures of the piece: on the guzheng this gesture – essentially a ‘colour trem’- exploits the LH side of the instrument, where there is a little cluster of 3-4 strings that are heard as ‘approximately Eflat’. The violin, cello and piano simulate this same ‘microtonal space’ in various ways on their own instruments. The challenge in making this tuning was trying to make a chromatic melody a feasible prospect: the result combines open pitches with ‘bendings’ to formulate the desired intervallic shapes, with intensely expressive results.

Dylan Lardelli: ‘Shells’:

In Shells Dylan Lardelli opts for a conventional ‘D minor’ tuning for the highest register whilst each of the lower octaves differs slightly. In the lower two registers the pitches in common (making octaves) help to maximise harmonic resonance (which is a particular feature of this work), while the ‘altered’ pitches in each register offer numerous harmonic ‘escapes’ from the pentatonic mode. You will also note the composer has retained the pitch ‘A’ in each octave, a nod to guzheng convention while subtly shifting the tonal palette.

Techniques

Guzheng players use both hands to play the instrument, usually with plectra attached to individual fingers to produce an incisive, bright tone. Both the hands pluck and strum the strings In the main playing area on the right hand side of the bridges. Timbral variety is produced by using finder tips (for a very much softer, less distinct tone) and by playing at different positions on the length of the strings (i.e. closer to the nut for a more brittle tone). Octave harmonics are readily produced.

An outstanding feature of the instrument is the way the left hand also provides colour by bending the string on the LH side of the bridge, producing a rich vocabulary of expressive bending gestures from microtonal vibrato to glissandi over the range of up to around 4 semitones.

The bending also allows pitches that lie between the pentatonic pitches to be accessed–e.g. to fill out a major or minor scale, or even a chromatic scale. The pitch content of chords is generally limited to the available strings although it is quite possible to alter the pitch of one string in a chord played entirely by the right hand, it is impossible to alter any pitches in chords played with both hands for obvious reasons.

Here are some examples of pitch bends:

Gao Ping: Feng Zheng

In the above example you can see the initial G is produced on the F£ string before releasing the left hand, the following gesture is produced from the open string bending it up and down by a minor 3rd rhythmically.

Lardelli: shells

In the above example an ebow is used to amplify an open string which is then adjusted by the left hand. This takes time to sound and the string will always need to be stimulated before a vibration can be established, hence the accent on the first note.

Ker: Time Bends in the Rock

the instructions for Kers work include various indications for bending pitches from, and to, fixed and approximate positions.

In the above example the end pitch is not specified, longer arrows indicate wider displacement, shorter arrows indicate more subtle inflections.

In the above example from Jeroen Speaks Silk Dialogues VII the composer has chosen a different notation, using single and double arrows over the open strings combined with the exact pitch required in parenthesis.

Bowing is very effective and can be used to produce a rich sul pont (bowing close to the bridge) or ‘tinny’ timbre (using a lighter stroke). Apart from the top and bottom strings, it is challenging to isolate individual pitches at high speed, while sweeps across the strings are effective.

Jeroen Speak : Silk Dialogues VII

In the example above you’ll see the right hand bows the lowest two strings while the left hand plucks, the bow is then swept up and down across the entire 21 strings while the left hand does the same on the left hand side of the soundboard. You notice exact pitches haven’t been indicated for the pitches behind the bridges as they cannot be predetermined.

In contrast with the characteristically bright, well-defined sound of the guzheng, the sound world available on the LH side of the bridge is ethereal and indeterminate in terms of tuning. This side of the instrument is not ‘tunable’ and the residual tunings are quite unpredicatable – handfuls of pitches are very close together, despite covering a much larger span on the other side. Both Dorothy Ker and Jeroen Speak exploit it in their pieces.

COPYRIGHT NOTICE All pages and content on this site are subject to copyright and cannot be used for any purpose without the editors consent